Echinococcus granulosus/E. canadensis

Contributor: Emily Jenkins, Lydden Polley, Janna Schurer and Karen Gesy

Biology: Cestode (tapeworm) in the Family Taeniidae. Identified as a zoonoses in Canada since 1882. There are many strains/species within the E. granulosus complex that transmit among different assemblages of hosts around the world. Only the cervid strain (G8/G10, also known as E. canadensis) is present in Canada, in all regions where wolves have been historically present (i.e. everywhere except the Atlantic provinces).

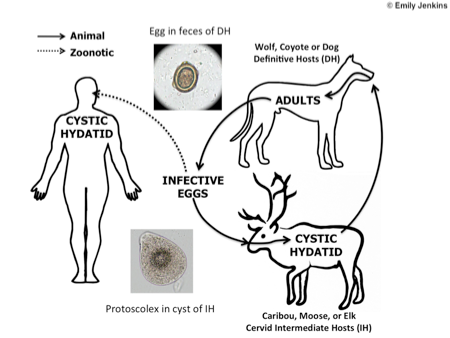

Life Cycle: Adult cestodes (2-11 mm in size) live in the small intestine of carnivore definitive hosts (wolf, coyote, and dog). Eggs (32-37 µm in diameter) are shed in faeces and are indistinguishable from those of other taeniid (Taenia species) cestodes. Eggs are immediately infectious and extremely environmentally resistant. Cervid (moose, caribou, elk, or deer) intermediate hosts ingest the eggs on vegetation, on the soil surface or in surface water. In the intermediate host, larval tapeworms (protoscolices) develop in large, single chambered cysts (unilocular hydatid cysts) in the liver or lungs. A single cyst can contain many protoscolices. The life cycle is completed when a carnivore ingests a cyst in the cervid tissue, through predation or scavenging.

Figure 1: Life cycle of the cervid strain of Echinococcus granulosus (E. canadensis) in northern North America. The larval (or metacestode) stage takes the form of a unilocular hydatid cyst (cystic hydatid).

Transmission: Most human infections in Canada are thought to be acquired through accidental consumption of eggs shed in faeces of dogs that hunt or scavenge wild cervids. People may also become infected through consumption of eggs shed in faeces of wild carnivores that have contaminated wild berries or surface water. As eggs are sticky, immediately infective, and environmentally resistant, it is possible that eggs can stick to perianal fur of infected dogs or wild carnivores. People do NOT become infected through consumption of cysts in harvested cervids.

Prevalence: 180 cases reported in Canada in 1948-1955, 108 hospitalized cases between 2001-2005. Not a nationally notifiable disease in people.

Susceptible Populations: Indigenous and northern populations where cervids are routinely harvested.

Symptoms: Symptoms may take many years to develop and depend on cyst size and location (often lungs with the cervid strain). Cysts may cause few or no symptoms, particularly in the lungs, unless they get very large or rupture, which can result in anaphylactic shock (severe allergic reaction) and/or seeding of larval stages. Liver cysts can result in abdominal pain. Occasionally, cysts may occur in abnormal locations, such as the brain, causing other problems.

Treatment: Cases of the cervid strain in Canada are often managed conservatively, with repeated monitoring through medical imaging to determine if the cyst is growing. Options include aspiration of the cyst, surgical removal, and/or long term therapy with parasiticides such as albendazole.

Control Measures: Good practices include disposing of offal from hunted cervids by deep burial or burning, dog population control and civic regulations for free-roaming dogs and pooper-scooping, good hand hygiene following handling of dogs, trapped or hunted wolves and coyotes, and faeces. Dogs with access to cervid carcasses should be dewormed using praziquantel or another effective cestocide on a monthly basis to eliminate infections before eggs are shed in faeces. Eggs are resistant to most chemical disinfectants, but are killed by temperatures colder than -80°C for 3-5 days, and have decreased survival in hot, dry conditions. At consumer/food handler level, thorough washing of fruits and vegetables is recommended, as well as effective filtering of untreated surface water prior to consumption.